Salt on your lips, wind in your ears, and no one holding a phone at arm’s length — that’s the first sign you’ve stepped off the algorithm’s map. In a world where the same five views loop through our feeds, the real thrill now is finding places that still feel secret, slow, and stubbornly themselves.

This is travel that swaps staged moments for quiet shocks of wonder, stranger’s kindness, and landscapes that rewire what you thought beauty looked like. Ahead are eighteen such places, and a different way to move through them — lightly, curiously, and fully present for you

1. Faroe Islands

And so we start with the Faroe Islands — a set of 17-or-so little islands (officially 17 inhabited) in the North Atlantic, self-governing under Denmark but with their own identity. steep cliffs plunging into the sea, narrow fjords, turf-roofed houses, sheep grazing everywhere. The population is small — about 54,500 as of 2024.

despite the dramatic scenery you can access, it still feels remote, un-over-pinked, un-over-filter-ed. There’s a strong local culture (fishing, wool, tradition) and they’re actively trying to avoid becoming just another “influencer hotspot”. For example, tourism income doubled to €125 million in 2023, yet the locals are talking about how to preserve authenticity.

Practical Information:

- Peak season / off-peak: May–September is the best weather window; winters are wild, with storms and very short daylight.

- How to reach & explore: You can fly into the capital Tórshavn (on Streymoy) from Denmark/Scotland, then rent a car or use public transport. Tunnels and bridges link many islands — recently there’s an 11.2 km undersea tunnel with a “roundabout” below sea level (yes, you read that right).

- Ideal duration: 5–7 days gives you a good taste; longer if you’re hiking remote islands.

- Must-try local experiences: Sea-eggs and langoustines in a harbor tavern; ferry over to a tiny village and walk above dramatic cliffs; watch thousands of puffins at dusk.

- Budget considerations: On the Nordic side in price — food and lodging cost more than many places in Europe; but staying in guest-houses or B&Bs off the main islands helps.

- Cultural etiquette tips: Respect nature: many trails are un-guarded and weather can switch fast. Ask before photographing locals, especially sheep farming operations.

- Photography opportunities: Think dramatic: waterfalls cascading into fjords, sheep on green cliffs, turf-roof houses in mist. But also—avoid the “everyone here does the same selfie” trap by going off the beaten path.

2. Isle of Eigg (Scotland)

Just over 3,000 ha (~30 km²) in area, with a population under 100 people. It lies off the west coast of Scotland, south of Skye — so you get remoteness without having to charter a private plane. The island community bought the land in 1997 and manage things themselves via the ‹Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust.

So when you visit, you’re experiencing something less “tourist-industrial” and more “real community place”. The terrain is diverse: volcanic plug An Sgùrr rises to ~393 m.

Visiting here feels like stepping out of time. Quiet bays, moorland, white sand “singing sands” that squeak underfoot. The wildness is tangible.

Practical information:

- Peak/off-peak: Summer (June–August) offers best weather and more ferry services; shoulder seasons (May, September) are quieter.

- How to reach & explore: Ferry from Mallaig (mainland Scotland) to Eigg; once there, walking, biking, kayaking. No big roads.

- Ideal duration: 3–4 days enough to soak in the place; longer if you hike or just relax.

- Must-try local experiences: Hike up to An Sgùrr for fantastic views out to the Hebrides; beach at Laig (“singing sands”); stay in a community-run guesthouse and chat with locals.

- Budget considerations: More affordable than many islands; but fewer amenities means you’ll need to plan ahead (food/ferry).

- Cultural etiquette tips: Small community: stay respectful, purchase local goods, stick to footpaths so you don’t disturb wildlife or crofting operations.

- Photography opportunities: Dawn on the ridge at An Sgùrr; quiet beach shots with glimmering sand; panoramic views out to sea.

3. Svaneti (Georgia)

This is the kind of place where you feel you’re off the grid (in the best sense). Svaneti is a mountainous region in northwest Georgia, in the Caucasus, filled with remote villages, medieval stone towers, and towering peaks like Mt Shkhara (~5,201m) and Mt Ushba (~4,710m). The sub-region “Upper Svaneti” is even a UNESCO World Heritage site, noted for its villages and defensive tower-houses.

ancient culture meets wild nature. You’ll find villages where the language, food traditions, and architecture feel rooted in centuries past. And yet you can walk alpine trails, ski in winter, or just relax in a homestay. It’s rare to find a place this dramatic and yet still relatively un-spoiled by mass tourism.

Practical information:

- Peak/off-peak: Best seasons are late spring through early autumn (May–September) for hiking; winter has snow and skiing but roads may be harder.

- How to reach & explore: Fly into Tbilisi or Kutaisi in Georgia, then drive/ride to Mestia or Ushguli in Svaneti. Some roads are winding mountain passes. Once there, trekking, village-hopping, staying with locals.

- Ideal duration: 4–6 days gives you village stays + at least one serious hike.

- Must-try local experiences: Stay in a Svan tower-house; try Georgian mountain cuisine (khachapuri, hearty stews); hike to remote glacier view or alpine meadow.

- Budget considerations: Georgia is generally affordable (lodging, food). Mountain area may cost more due to remoteness.

- Cultural etiquette tips: Respect local traditions — Svan people have their own dialect and customs. Ask permission before taking photos of homes. Dress modestly if entering local churches/chapels.

- Photography opportunities: Stone towers in Ushguli against the snow-capped peaks; wild meadows and mountain passes; dramatic dusk light in the high valleys.

4. Lofoten’s Remote Islands (Værøy & Røst) – Norway

the broader Lofoten Islands archipelago is already known, but if you pick the far-flung bits like Værøy and Røst you lean into genuine remoteness and fewer crowds. Værøy is ~15.7 km² and home to ~100% of its municipal residents; the bird-life is off the charts (40,000 pairs of Atlantic puffins at one cliff area).

Røst, further out, still flatter and more expansive sea-wise, is ideal for a slower, almost cinematic kind of travel. you get the Arctic-archipelago aesthetics — dramatic peaks, eerie winter light, very few humans, plenty of seabirds, and that “just you and nature” vibe. It’s perfect if you want beauty without big crowds.

Practical information:

- Peak/off-peak: Summer (June–August) for long daylight and easier ferry/plane access; late autumn/winter for northern lights but weather is more challenging.

- How to reach & explore: Fly or ferry from Bodø to Værøy or Røst. Once there, use local guides, boats to bird-cliffs, hike the trails.

- Ideal duration: 3–4 days minimum; 5–7 if you want to roam both islands and maybe take a boat trip.

- Must-try local experiences: Dawn on a remote cliff watching seabird colonies; stay in a fishing-village guesthouse; kayak around archipelago.

- Budget considerations: These are smaller islands — lodging options exist but fewer than big resorts; costs can reflect remoteness.

- Cultural etiquette tips: These are working-fishing communities — respect local livelihood, avoid disturbing bird-nesting zones, keep noise minimal.

- Photography opportunities: Bird cliffs with puffins in flight; sea-stack silhouettes at dusk; remote village with red fisherman cabins and turquoise sea.

5. Yakushima (Japan)

Yakushima is one of those places that feels like Earth’s natural memory. It’s an island off southern Japan (about 60 km from Kyushu) where 90 % of the land is forested, and a significant portion is protected.The forested zone of ~10,747 ha (21 % of the island) is a UNESCO World Heritage site thanks to its ancient cedar trees (called “Yakusugi”), big rainfall (over 8,000 mm at high points) and rich biodiversity.

mossy forest floors, huge twisted trunks, mountain ridges rising to ~1,900-2,000 m, mist, streams. It’s still less known internationally compared to big tourist spots, which means it retains a kind of hush. yes you’ll see gorgeous shots, but you won’t (yet) feel like you’re battling influencers. It’s more about connection with nature, slowing down.

Practical information:

- Peak/off-peak: Spring to autumn (April–November) is most comfortable; winter is cold and trails may have snow/ice.

- How to reach & explore: Fly into Yakushima from Kagoshima or via ferry; once on the island use local buses or rental car, then hike trails like to Jōmon Sugi (ancient cedar).

- Ideal duration: 3-5 days. Enough to do forest hikes, coastal views, maybe a mountain hike.

- Must-try local experiences: Hike to Jōmon Sugi (might take 4–5 hours each way); stay at a lodge in forest; soak in hot springs (onsen) after a day of hiking.

- Budget considerations: Japan prices apply; remote island lodging can cost more than mainland rural stays.

- Cultural etiquette tips: The forest is sacred — stick to trails, don’t feed wildlife, keep quiet, remove trash. Japanese hospitality values respect.

- Photography opportunities: Giant ancient cedars draped in moss; misty high-mountain ridges; contrast of lush forest and dramatic coastline.

6. Socotra, Yemen – the place that still feels like another planet

Socotra feels like the place the rest of the world forgot, in a good way and a scary way. Botanists have counted more than 825 plant species, with about one-third endemic, including the umbrella-shaped dragon’s blood tree which is listed as Vulnerable. Those trees act like giant water collectors, catching moisture in their canopies and feeding the parched soil below.

Recently, researchers and local communities have been sounding the alarm: stronger cyclones, invasive goats and political instability are hitting these old trees hard, and some models suggest wild populations could crash within a few centuries without help.

Practical Information:

- Best season: October–March for calmer seas and milder heat (around mid-20s to low-30s °C).

- Getting in: Seasonal/charter flights usually route via mainland Yemen or occasional Gulf hubs; you almost always join a pre-arranged tour.

- On-the-ground realities: Expect wild camping, simple guesthouses, limited Wi-Fi and very basic infrastructure.

- Budget ballpark: Multi-day tours typically bundle permits, food, transport and guiding; it’s not cheap, but there’s almost no way to “go it alone” on the cheap.

- Low-impact behaviour: Stick to existing tracks, don’t climb dragon’s blood trees or break branches, keep drones away from wildlife, and pack out every bit of trash.

7. Flores & Corvo, Azores – Europe’s quiet biosphere bubble

Flores and Corvo sit way out on the western edge of the Azores, literally some of the last bits of Europe before the open Atlantic. Flores has dramatic cliffs, crater lakes and only about 4,000 residents, while Corvo shrinks that down to a single village of roughly 400 people. Both islands, plus their surrounding waters, are part of UNESCO’s World Network of Biosphere Reserves, which means conservation and community life are supposed to move in step instead of competing.

Flores and Corvo are huge for seabirds. Together they form an Important Bird Area of more than 210,000 ha, key for Cory’s, little and Manx shearwaters, roseate terns and other species that feed and nest on the cliffs and offshore stacks. That’s why some hiking paths are seasonal or gently restricted, and why local guides focus on weather windows that work for people and birds.

Practical Information:

- When to go: Late May–October for softer seas, more ferries and green landscapes; June and September balance decent weather with fewer visitors.

- How to get there: Fly from mainland Portugal to Flores; hop by small ferry or boat tour to Corvo for a day trip or overnight.

- How long to stay: Flores: 3–5 days for crater lakes, waterfalls and coastal trails. Corvo: 1–2 days if you love walking, birdlife and silence.

- Costs & booking: Limited beds and rental cars in high season; booking months ahead is smart for July–August.

- Rural etiquette: Close gates, keep noise down near nesting cliffs, and buy from village cafés and cooperatives where you can.

8. Raja Ampat, Indonesia – the reef’s control room

Raja Ampat is where marine stats get ridiculous. Researchers have logged more than 1,600 reef fish species and 550+ coral species here, which amounts to roughly three-quarters of all known coral species on Earth. It’s often called the global “epicenter” of marine biodiversity, and you feel that the second you drop into the water: reef walls stacked with fans, sharks cruising, mantas at cleaning stations, schools of tiny fish doing their own choreography.

What gives your article a fresh angle is the tension between protection and extraction. Raja Ampat is a UNESCO Global Geopark and much of it lies inside marine protected areas funded partly by visitor fees. At the same time, nickel mining for EV batteries has been expanding around the region; in 2024–2025, Indonesia revoked the licenses of four mining companies in Raja Ampat after environmental breaches, but one large operation continues on Gag Island outside the core protected zone.

Practical Information:

- est conditions: Roughly October–April for calmer seas, clearer water and manta season; July–September can bring stronger winds.

- Access chain: Fly to Sorong, speedboat or ferry to Waisai or a resort jetty, then smaller boats to homestays or liveaboard.

- Where to sleep: Options run from family-run homestays on stilts over the water to high-end eco-resorts and liveaboard dive boats.

- Costs to expect: Marine park entry fees are mandatory and help fund patrols; food, fuel and logistics make this pricier than average Indonesia, but homestays keep it far from “only for luxury travelers.”

- Good habits: Reef-safe sunscreen, excellent buoyancy control, no fin-kicking the coral, and a mindset that treats each dive as visiting someone else’s home.

9. Ladakh, India – high-altitude stillness with a heartbeat

Ladakh sits in the rain shadow of the Himalaya as a high-altitude cold desert. The main town of Leh stands at about 3,500 m above sea level with intense sunshine, big temperature swings and only around 100 mm of precipitation a year. That climate gives Ladakh its sharp light and clear skies, but it also means life depends on snowmelt channels and traditional water-sharing systems. So when travelers talk about “using less water in the guesthouse,” that’s not just a vague eco-tip, it’s very literal.

monasteries perched above barley fields, villages that still work on short growing seasons and festivals timed to lunar calendars. The old town of Leh has even appeared on the World Monuments Fund’s list of endangered sites, partly because heavier rains linked to climate change are stressing buildings that evolved in a near-rainless climate.

Practical Information:

- Weather & timing: June–September, with Leh daytime highs up to about 25°C and cold nights. April–May and October are quieter but can be snowy or chilly.

- Getting there: flights into Leh (acclimatisation days are non-negotiable). overland from Manali or Srinagar once high passes open for the summer.

- Trip length sweet spot: 7–10 days for a couple of valleys plus acclimatisation; more if you’re trekking.

- Health & safety: Altitude tablets in consultation with a doctor, hydrate well, no big hikes on day one or two.

- Respecting culture: Dress modestly, circle stupas clockwise, stay quiet during prayers, and ask before photographing people or ceremonies.

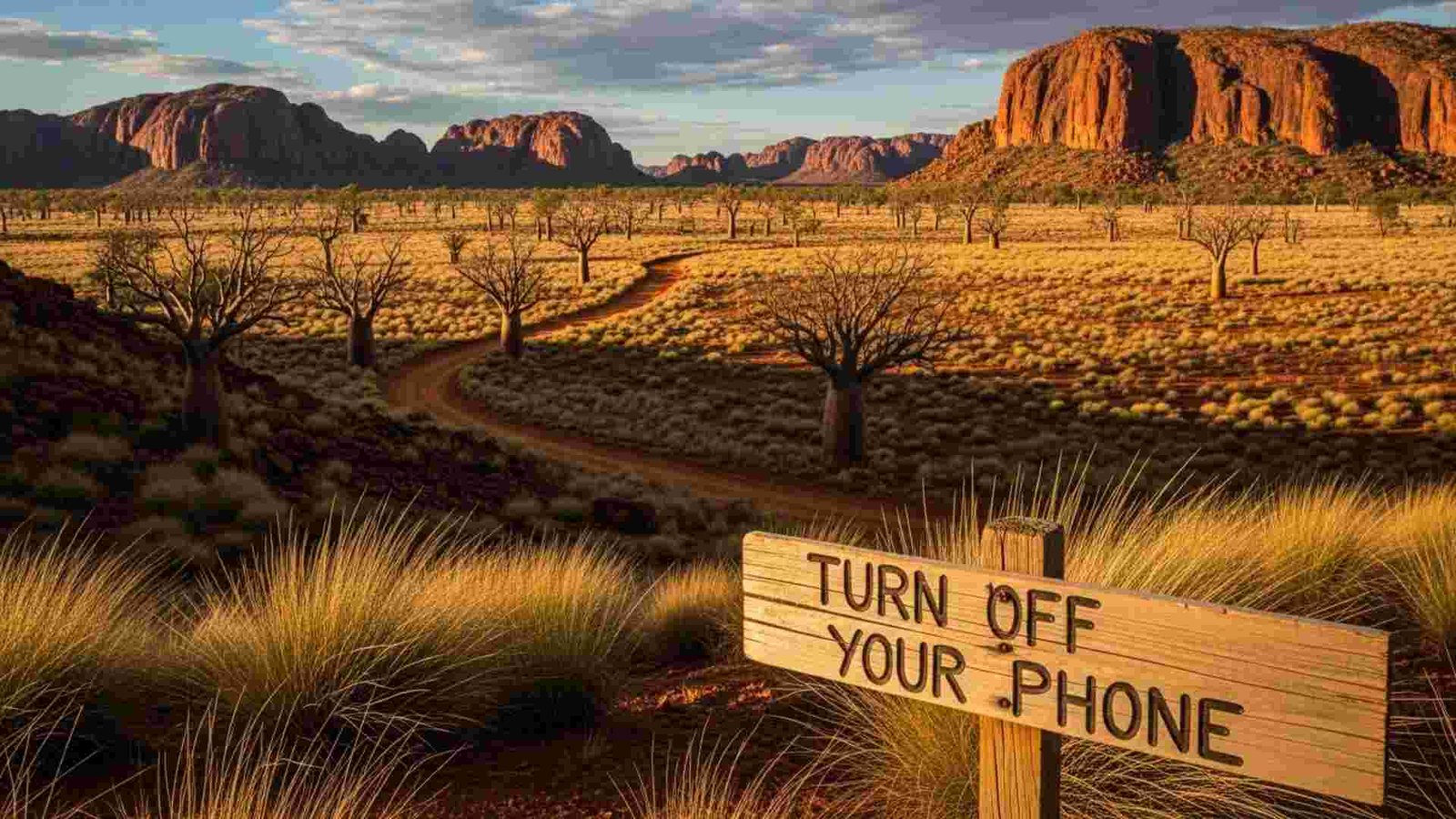

10. The Kimberley, Australia – wilderness at “turn off your phone” scale

The Kimberley fills the entire north-west corner of Western Australia with about 423,500 km² of rugged plateaus, gorges and coastline — roughly three times the size of England — and yet has only around 34,000–35,000 residents. Tourism boards rightly call it one of the world’s last wilderness frontiers, and that’s not just marketing; in the dry season you can drive for hours between roadhouses and still feel like you’re nowhere near the edge.

The lesser-known angle here is how deep the human history runs. Archaeological and cultural evidence points to Aboriginal presence in parts of the Kimberley stretching back tens of thousands of years, with rock art galleries and songlines that predate many “ancient” sites elsewhere.

Practical Information:

- Seasons: best for road trips, gorges and camping. many roads close, some cruises still run, waterfalls at their wildest.

- Ways to explore: 4WD along the Gibb River Road, coastal cruises from Broome or Wyndham, or scenic flights over places like Mitchell Falls and the Buccaneer Archipelago.

- Time needed: At least 7–10 days for a one-way Gibb River crossing; 2–3 weeks if you want both inland gorges and some coastal time.

- Budget snapshot: Fuel and vehicle hire are big line items; camping keeps costs down, while cruises and luxury lodges push the trip into “once-in-a-lifetime” territory.

- Key etiquette: Follow crocodile warning signs, respect Aboriginal land and permit rules, keep to marked tracks, and leave remote camps and waterholes spotless.

11. Chachapoyas, Peru – cloud-forest archaeology instead of crowded ruins

Chachapoyas feels like Peru’s alternate timeline. Long before the Inca, the Chachapoya “Cloud Warriors” built fortified towns and cliff tombs across these misty highlands from around AD 800 onwards, trading between the Andes and the Amazon. Their most famous stronghold, Kuélap, sits on a ridge at over 2,900 m, with massive stone walls and hundreds of circular houses packed into a single hilltop.

Then there’s Gocta, the region’s poster child for how “hidden” a place can be in plain sight. Locals always knew the 771 m waterfall; the outside world only caught on after an expedition in 2002 and a press splash in 2006. It’s often listed among the tallest waterfalls on Earth, even if rankings vary, and the path in from Cocachimba threads through sugarcane fields, orchids and cloud forest rather than souvenir rows.

Practical Information:

- Best time to go: Drier months roughly May–October for better trail conditions; expect mist and occasional showers year-round because… cloud forest.

- How to base yourself: Town of Chachapoyas (around 2,230 m) as a hub, or small lodges near Cocachimba for Gocta views from your balcony.

- Key days to plan: 1 day Kuélap (when access is open), 1 day Gocta, 1 extra for secondary sites or just wandering local markets.

- Budget feel: Food and guesthouses are far cheaper than Peru’s big-name hubs; guided day trips to Kuélap/Gocta are usually the main “big” expense.

- Good traveller behaviour: Use local guides, stick to marked paths near fragile archaeological structures, and keep noise low inside the ruins and forests.

12. Kotor’s Hinterland, Montenegro – beyond the bay, up the switchbacks

Most people stop at the bayfront and call it a day. Your reader doesn’t. The Kotor Serpentine Road climbs over 900 m from the bay in a series of about 25 tight switchbacks, a historic route once used for trade and military access. As you gain height, you leave the cruise-ship scene behind and swap it for goat bells and old stone farmhouses. At the top of this climb, the village of Njeguši still cures its famous prosciutto and cheese the traditional way; tasting it in a backyard smokehouse hits very differently than ordering a plate in a waterfront restaurant.

Push a bit further and you’re in Lovćen National Park, where trails lace through black pine forests up to the mausoleum of Petar II Petrović-Njegoš, perched on Jezerski Vrh with sweeping views over the bay and inland mountains. There’s even a new cable car option from Kotor to the high ground, which means one person in a group can take the scenic glide while another takes the hairpin road and you all meet above the clouds. This whole area is where your “anti-Instagram” traveler realises Montenegro is not just about old towns and yachts; it’s a living highland culture with its own flavours and stories.

Practical Information:

- How to get up: Self-drive the Serpentine Road (daylight only, slow and careful), join a small-group tour, or ride the Kotor–Lovćen cable car and connect with local transport at the top.

- What to combine in one day:

- Morning: serpentine viewpoints.

- Midday: Njeguši for prosciutto, cheese and village walks.

- After noon: Lovćen hikes + Njegoš mausoleum.

- When to go: Late spring to early autumn for clear roads; July–August is hotter but evenings in the mountains stay cooler than on the coast.

- Car & road reality: Road is narrow with blind bends; nervous drivers might prefer a local driver or tour.

- Respect points: Take it slow through villages, dress modestly at the mausoleum, and support local smokehouses and cafés instead of just snapping a photo and leaving.

13. Albania’s Accursed Mountains – Europe’s wildest corner still sleeping

The Accursed Mountains (Prokletije/Bjeshkët e Nemuna) sit right in the corner where Albania, Montenegro and Kosovo meet. They’re one of Europe’s most glaciated ranges south of the Alps, with relief differences up to 1,800 m in valleys like Valbona and Grbaja, and evidence of long, powerful ice-age glaciers carving those troughs. This is not polished “alpine resort” country; villages are small, often only lived in seasonally, and winters cut off some valleys for weeks at a time.

The biodiversity story is huge. Botanists have documented around 1,611 wild plant species in the Albanian part alone, with about 50 endemic or endangered species and a big pocket of arcto-alpine relic flora that survived from glacial times. Wildlife still includes brown bears, wolves and the critically endangered Balkan lynx, plus over 140 butterfly species, making it one of Europe’s richest butterfly areas.

Practical Information:

- Key trekking routes: Valbona–Theth pass (around 1,795 m), plus sections of the Peaks of the Balkans Trail linking all three countries.

- When it works best: roughly June–September; snow can linger on high passes early in the season.

- How to base yourself: Family guesthouses in Valbona, Theth or Montenegrin villages around Prokletije National Park (established 2009, about 168 km²).

- Safety mindset: Terrain is serious mountain country; check recent trail conditions, carry proper gear, and consider a local guide, especially outside peak season.

- Impact & respect: Book directly with local guesthouses where possible, keep to marked trails, and remember that many residents are juggling farming, forestry and tourism together.

14. La Gomera, Canary Islands – the island almost everyone skips

La Gomera sits just off Tenerife, yet only about 1% of Canary Islands visitors make it over. The island is compact at around 369–371 km², rising to 1,487 m at Alto de Garajonay, with deep ravines radiating from a central plateau. Most of that plateau is covered with laurel forest, a humid, evergreen ecosystem that once blanketed much of southern Europe. Today, Garajonay National Park protects a big chunk of it and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site; laurel forest covers about 70% of the park.

The fun twist for your reader is how walkable the whole island is. There’s a network of over 600 km of marked trails linking villages, ravines, palm groves and forest, which means you can treat the whole island as one big trail system rather than a set of isolated “sights.” You can hike one day through misty forest where tree trunks wear moss jackets, then drop into a warm valley lined with banana terraces and black-sand beaches the next. And because Gomera is also a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, there’s a genuine push to keep that slow, rural character intact.

Practical Information:

- Getting there: Fly to Tenerife, then hop a ferry (about 50–60 minutes) to San Sebastián de La Gomera.

- Best season feel: ear-round mild climate; summer highs around 27°C on the coast, cooler in the high forests.

- How to move: Bus network plus rental cars; serious hikers can base in valleys like Valle Gran Rey and use trails as a daily transport system.

- Trip style: 5–7 days of point-to-point hiking or day hikes; mix forest walks, ridge views (Mirador de Abrante) and low-key coastal evenings.

- Good habits: Stay on signed paths to avoid erosion in steep ravines, keep noise down in Garajonay’s denser sections, and support local casas rurales and small restaurants.

15. Patagonia’s Aysén Region, Chile – the long way round on purpose

Patagonia gets the headlines, but Aysén is where Patagonia still feels genuinely remote. It’s Chile’s third-largest region by area yet its most sparsely populated, with just over 102,000 people recorded in 2017. The iconic Carretera Austral road threads through this emptiness, connecting fjords, temperate rainforests and glacier valleys while serving only about 100,000 people along its entire length.

Nature-based tourism here has grown fast in the last decade, challenging older economies built on logging, ranching and extraction. You see that shift in places like Puyuhuapi or Lago Verde, where guesthouses and trailheads now sit beside working farms. A 2025 account of the Across Andes ultra-distance bike route describes riders covering 1,000 km with around 15,000 m of climbing through Aysén, passing Coyhaique, Queulat National Park and Puyuhuapi along rough gravel and ever-changing weather.

Practical Information:

- Main gateway: Coyhaique as practical base; fly in via Balmaceda airport, pick up a car or bike, then head north or south.

- Best season: Southern summer (Dec–Mar) for long days; spring and autumn for quieter roads and more dramatic weather.

- Typical pace: 10–14 days for a chunk of the Carretera; more if you want serious detours into parks and fjords.

- Cost reality: Remote fuel and food prices, plus higher costs for boat transfers and excursions; wild-camping and simple hospedajes help balance the budget.

- Respect checklist: Stick to established campsites and tracks in fragile temperate rainforest, pack for cold rain even in summer, and remember local communities are still figuring out how tourism fits alongside traditional livelihoods.

16. Fogo Island, Canada – North Atlantic edge with a purpose

Fogo Island sits off Newfoundland’s northeast coast and holds just over 2,100 residents across several small communities, down about 5.7% since 2016. It was once entirely defined by cod fishing; when the fishery collapsed, the island faced a familiar rural story of outmigration and decline. The twist is what happened next. The Shorefast Foundation, a registered charity, stepped in to reframe Fogo as a model of place-based economic development, focusing on local culture, craft and the wild North Atlantic environment as its main assets.

The most visible symbol is the Fogo Island Inn, a striking modern building on stilts above the rocks that runs as a social enterprise: profits are reinvested back into the community, and guests are paired with local “community hosts” who show them the island beyond the dining room view. But you don’t have to stay there to feel the effect. Artist studios dot the coastline, traditional fishing stages still cling to coves, and walking trails link villages where woodpiles and saltbox houses tell you this is a working landscape, not a themed museum.

Practical Information:

- Getting there: Drive through Newfoundland to the Farewell ferry terminal, then take the public ferry to Fogo Island; car strongly recommended once you’re on the island.

- Seasonal feel: Late spring to early autumn for hiking, icebergs in early season, and festivals; winters can be harsh and quiet but beautiful if you’re prepared.

- Where to stay: Fogo Island Inn at the high end, plus B&Bs, rental homes and small inns in communities like Joe Batt’s Arm or Tilting.

- Budget snapshot: Groceries and basics are limited and pricier than the mainland; planning meals and booking ahead are key.

- Cultural etiquette: People are friendly but private; a wave and a short chat go a long way. Support local crafts, respect working wharves and keep to paths around fragile coastal vegetation.

17. Wadi Rum’s Quiet Valleys, Jordan – desert as a living archive

adi Rum stretches across about 74,000 ha of sandstone and granite in southern Jordan, near the Saudi border, and is the country’s largest wadi. It’s famous for its red sands and rock arches, yet the deeper story is written on the stone itself: petroglyphs, inscriptions and archaeological remains record about 12,000 years of human presence, from early hunter-gatherers to caravan traders. Standing in one of the smaller side canyons and tracing those carvings with your eyes feels like time travel without the headset.

The protected area is co-managed with local Zalabieh Bedouin communities, who have shifted from herding and camel caravans to eco-adventure tourism: guiding hikes, driving 4×4 tours, and running desert camps. Many camps now sit away from the busiest zones, tucked into quiet valleys where the night sky still feels untouched. For your reader, the anti-Instagram move is simple: book with a Bedouin-run camp that limits group sizes, spend extra time walking rather than just driving, and treat the silence as the main attraction.

Practical Information

- Access: About 60 km from Aqaba; visitors register at the Wadi Rum Visitor Centre and join local guides from there.

- Best times: Spring and autumn for comfortable days and cool nights; summer can be very hot, winter can be cold at night.

- How to stay: Traditional-style Bedouin camps, simpler “wild camping” setups with a guide, or protected rock shelters on trekking routes.

- Activities: Half- or full-day 4×4 tours, camel rides, rock scrambles, long hikes and stargazing; some visits include sunrise or sunset viewpoints as standard.

- Good practice: Choose local operators, avoid off-trail driving in fragile zones, treat rock art with absolute care (no touching), and pack out any trash from campsites.

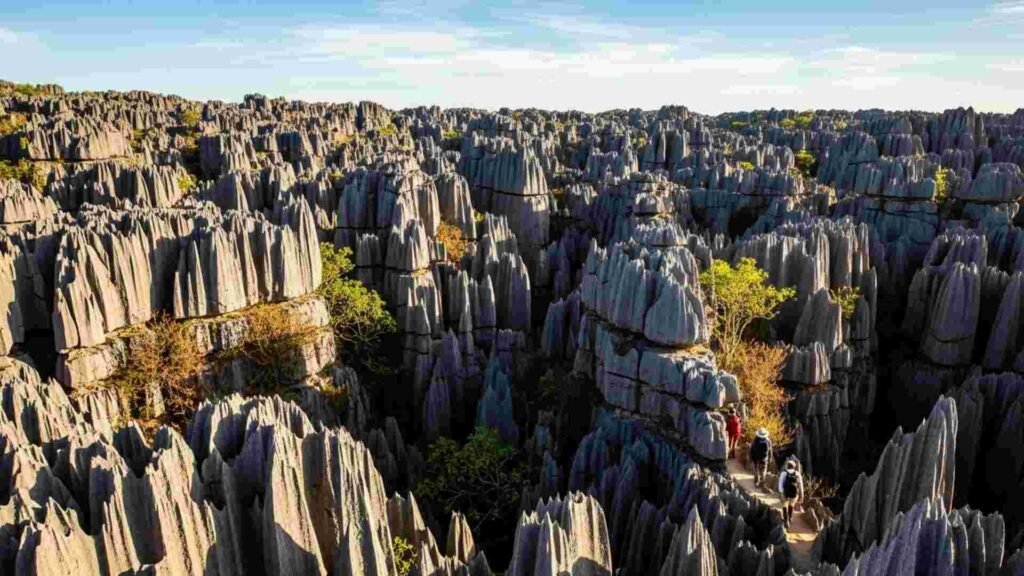

18. Tsingy de Bemaraha, Madagascar – the stone forest that bites back

Tsingy de Bemaraha looks like a fantasy drawing until you realise you’re actually walking through it. The reserve and adjacent national park protect a karst plateau where limestone has eroded into a “stone forest” of razor-sharp pinnacles, some reaching up to 100 m high. The Malagasy word tsingy roughly means “where one cannot walk barefoot,” which is both poetic and very literal once you see the rock edges. Together, the strict nature reserve (about 152,000 ha) and the park form part of the Andrefana Dry Forests serial World Heritage property, expanded in 2023 to include more western dry-forest reserves.

What’s less talked about is the biodiversity that threads through this stone maze: endemic lemurs leaping between rock towers, rare birds hunting along the cliffs, and dry forests that hold species found nowhere else. Footpaths, fixed ladders and suspension bridges guide visitors through sections of Grand Tsingy and Petit Tsingy so you can see the formations without trampling everything underfoot. A lot of the magic happens at the edges: sunset over the pinnacles from a viewpoint, or a quiet moment in a hidden canyon where the air feels cooler and full of bird calls.

Practical Information

- Location: Central-west Madagascar on the Bemaraha Plateau, around 250 km west of Antananarivo and 60–80 km inland from the west coast.

- Season window: Primarily accessible in the dry season (roughly April–November); roads can be impassable in heavy rains.

- Access pattern: Usually reached via Morondava and Bekopaka with 4×4 vehicles; trips often combine the tsingy with the nearby Avenue of the Baobabs.

- On-the-ground style: Guided only in core areas; expect harnesses or via ferrata-style sections in Grand Tsingy, and moderate fitness requirements.

- Low-impact rules: Follow guide instructions exactly, avoid wandering off trails, and keep group sizes small where possible to limit wear on ladders and paths.

Conclusion:

In the end, an “anti-Instagram trip” isn’t really about avoiding cameras. It’s about choosing places that still feel lived-in, where the culture is deeper than the captions and you’re a guest, not the main character. These 18 destinations reward slowness, curiosity, and the kind of respect that leaves no trace behind. If you travel with that mindset, you don’t just bring home better stories — you help keep these corners of the world wild, local, and wonderfully unruined for the next person who needs a break from the feed.