You stand up a little too fast, or in a dark room, and for one split second, you wobble. Or you step off a curb you didn’t quite see, and your heart does that little lurch before you catch yourself.

Most of us just laugh it off. “Whoa, lost my balance there.” We blame it on being tired, or clumsy, or just… getting older.

But what if it’s not just your legs? What if it’s a message, a quiet signal, from the most complex thing you own? What if your balance is a vital sign?

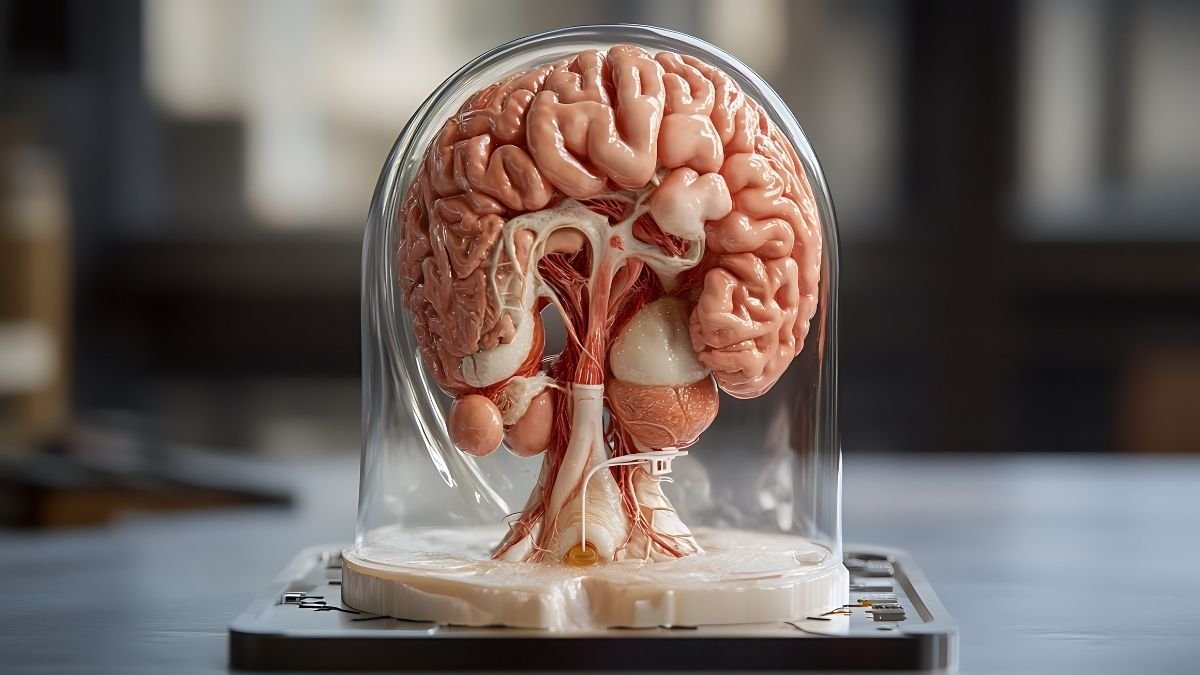

We tend to think of our brains as being for thinking—for memories, for emails, for worrying about bills. We think of our bodies as being for moving. The truth is, the two are inseparable. Your ability to stand, walk, and move smoothly is one of the most profound and data-heavy tasks your brain performs. It’s a constant, real-time neurological symphony. And when the symphony starts to sound a little “off,” it’s not an inconvenience. It’s a clue.

This article is about that clue. We’re going to explore the deep, intricate link between your physical stability and your brain’s health. More importantly, I’m going to give you a set of tools—a 12-test toolkit—that you can use at home. These aren’t just “tests”; they’re a way for you to listen in on that conversation between your brain and your body.

Why You Can’t ‘Just’ Stand: Your Brain’s 3-Part Balancing Act

Look, your brain is command central for… well, everything. But to keep you from toppling over, it’s not just one thing. It’s a team. Think of it like a three-legged stool. If any one leg gets wobbly, the whole thing gets unstable.

Your brain is constantly, and I mean constantly, processing data from these three systems:

- Your Eyes (The Obvious One)This is the one we all notice. Your eyes scan the horizon, tell you if the floor is level, and spot obstacles. It’s your brain’s most direct link to the outside world.

- Your Vestibular System (The Inner Ear Gyroscope)Deep inside your inner ear, you have this wild, tiny system of fluid-filled canals and organs. This is your body’s biological gyroscope. When you tilt your head, turn, or move up and down, that fluid sloshes around and tells your brain exactly where your head is in space. That seasick, dizzy feeling you get on a boat? That’s what happens when your inner ear feels motion, but your eyes see a static cabin. Your brain gets conflicting reports and freaks out.

- Proprioception (Your ‘Internal GPS’)This one is the coolest, and the one we never think about. It’s your body’s “sixth sense.” It’s your brain’s built-in GPS. It’s the constant, silent stream of information from millions of tiny sensors in your muscles, tendons, and joints, all telling your brain where every part of you is without you having to look. It’s how you can touch your nose with your eyes closed, walk in the dark, or know exactly how hard to grip an egg.

The ‘Little Brain’ That Runs the Whole Show: Your Cerebellum

Okay, so you have these three systems all screaming information at your brain—”The floor is tilted! We’re turning left! The ankle is rolling!”

Who listens to all this? Who makes sense of it?

That’s the star of the show: your cerebellum. It’s that little structure at the back of your skull, tucked underneath the main brain. And here’s the crazy part: while it’s only about 10% of your brain’s volume, it contains over 50% of all its neurons.

The cerebellum doesn’t start a movement. Your “thinking” brain (the cortex) sends the command, like “I’d like to pick up that cup of coffee.”

The cerebellum then acts as a powerful, real-time “movement editor” and “timekeeper”. It takes the sloppy “pick up coffee” command, instantly compares it to all the data from your Balance Triad, and fine-tunes it. It calculates the distance, the timing, and the exact muscle force needed to make the movement smooth, accurate, and coordinated.

When this system is healthy, your movements are fluid.

When this system is damaged or starts to fade, you get specific, testable problems:

- Ataxia: A word for uncoordinated, clumsy movements.

- Dysmetria: This is the big one. It’s the inability to judge distance or range. It’s “overshooting” or “undershooting” a target. It’s what we’re looking for in the coordination tests.

The Critical Link: When Balance Fades, It Can Signal Brain Changes

Here’s the takeaway. A decline in balance isn’t just a physical problem; it’s a primary symptom of aging that’s tied directly to changes in your motor, sensory, and cognitive functions.

A degenerating cerebellum, for example, leads to ataxia. But it’s even deeper than that. Neurologists warn that poor balance can be a red flag for other issues. Dr. Shari Rosen-Schmidt, a neurologist, says that an inability to stand on one foot for 20 seconds could be a reason to be “further evaluated for vascular problems”. Why? Because small blood vessel damage in the brain—a huge risk factor for stroke—can show up as poor balance.

While researchers look for complex biomarkers in spinal fluid or new blood tests, your balance is a powerful, real-world functional biomarker. A wobble is a physical symptom of what’s happening upstairs.

The statistics are sobering: 1 in 4 adults over 65 falls each year. 1 in 10 adults over 45 reports cognitive decline. These aren’t separate issues. They’re often two sides of the same coin.

But here’s the good news. This road runs both ways.

The act of balance and coordination training has been shown to improve brain health. Studies show coordination training can improve cognitive function and even increase the volume of the hippocampus (your brain’s memory center!).

This changes everything. It means balance isn’t just a symptom to watch; it’s a skill to train.

The 12 tests below are designed to pick apart that “Balance Triad.” We’re going to strategically challenge each of those three legs to see where the wobble is coming from. For example, the Romberg Test asks you to close your eyes. If you’re steady with eyes open but fall apart with them closed, we’ve learned something huge. The problem isn’t your cerebellum; it’s that your “internal GPS” (proprioception) has gone quiet, and you were using your vision to cheat. This is how we find the why.

Your 12-Test At-Home Check-In: First, a Promise: The 30-Second Safety Check

Listen. These assessments are designed to test your limits. That means you will feel unsteady, and that’s the point. But we have to be smart. Please, do this 30-second check before you start anything.

- Clear the Space: Do this in a well-lit area. Get rid of throw rugs, power cords, or anything else you could trip on.

- Use Support: Stand on a firm, non-slip floor. Have a sturdy chair, a kitchen counter, or a wall within arm’s reach at all times.

- Have a Spotter: If you know you’re at risk for falls, or you just feel nervous, ask someone to be in the room with you.

- Listen to Your Body: This shouldn’t hurt. If you feel sharp pain or true vertigo (the room spinning), stop immediately.

Category 1: Static Balance & Foundational Stability (Tests 1-4)

This first group checks your foundation. Can you hold your body still and stable?

Test 1: The Romberg Test

- What It Tracks: This is a classic. We’re testing your proprioception (that “internal GPS”) by seeing what happens when we “unplug” your vision.

- How to Perform:

- Stand with your shoes off, feet close together, side-by-side.

- Cross your arms over your chest or let them hang by your sides.

- Part A (Eyes open): Stand still for 30 seconds. A little swaying is normal.

- Part B (Eyes Closed): Now, close your eyes and hold for 30 seconds. Be near that counter!

- What the Results Mean: A “pass” is holding steady for 30 seconds in both. A “fail” (a positive Romberg) is if you only lose your balance or sway wildly when your eyes are closed. This is a huge clue that your brain is missing signals from your body’s GPS.

Test 2: The 4-Stage Balance Test (Positions 1 & 2)

- What It Tracks: This is a progressive test from the CDC’s STEADI program. We’re just narrowing your base of support bit by bit.

- How to Perform:

- Hold each position for 10 seconds. Don’t use a cane, and keep your eyes open.

- Position 1 (Side-by-Side): Stand with your feet touching, side-by-side. Hold for 10 seconds.

- Position 2 (Semi-Tandem): Place the instep of one foot so it’s touching the big toe of the other foot. Hold for 10 seconds.

- What the Results Mean: These are the warm-ups. If you can’t hold these for 10 seconds, it signals a basic balance deficit.

Test 3: The Tandem Stance (4-Stage Balance Test, Position 3)

- What It Tracks: This is the one that matters. It’s like standing on a tightrope. It’s tough, and it’s a key predictor of fall risk.

- How to Perform:

- Place one foot directly in front of the other, heel-touching-toe.

- Hold this for 10 seconds without stepping off the “line”. Test with each foot in front.

- What the Results Mean: This is a big one. The CDC states that an older adult who cannot hold this tandem stance for at least 10 seconds is at an increased risk of falling.

Test 4: The Single-Leg Stance (SLS)

- What It Tracks: Your ability to stand on one leg, which is essential for walking, climbing stairs, and catching yourself from a stumble.

- How to Perform:

- Stand on a firm surface, hands on your hips.

- Lift one foot off the floor, bending the knee. The raised foot shouldn’t touch your standing leg.

- How long can you hold it (max 30-45 seconds) without putting your foot down or moving your standing foot?

- Test both legs.

- What the Results Mean: As we’ll see in the table, this is a powerful check-in. That neurologist quote? She gets concerned if you can’t hold this for 20 seconds.29 A time under 10 seconds is a known fall risk predictor.

Category 2: Dynamic Balance, Mobility & Functional Strength (Tests 5-9)

Okay, standing still is one thing. Now, let’s move. This category checks your balance in motion, which also means we’re testing your functional leg strength.

Test 5: The Five Times Sit-to-Stand (5TSTS)

- What It Tracks: I love this test. It’s a no-nonsense measure of your functional leg strength and power. Honestly? Half of what people call “poor balance” is just weak legs. And strength is trainable.

- How to Perform:

- Sit in a sturdy chair with a firm seat (about 17 inches high). No armrests.

- Sit with your back against the chair, then fold your arms across your chest.

- On “Go,” stand up all the way and then sit back down all the way, five times, as fast as you can.

- Time starts on “Go” and ends when your butt hits the chair on the 5th rep.

- What the Results Mean: This is all about time. A score of $\ge$16 seconds has been shown to separate folks with a fall risk from those without. If you have to use your arms, that’s a “0” score and a clear sign we need to build strength.

Test 6: The Timed Up & Go (TUG) Test

- What It Tracks: This is one of the most common tests used by clinicians. It’s a mini-obstacle course: stand up, walk, turn, walk, sit down. It checks strength, gait speed, and dynamic balance all at once.

- How to Perform:

- Put a standard armchair against a wall (so it won’t slide).

- Measure 3 meters (or 10 feet) and put a marker on the floor.

- Sit fully back in the chair.

- On “Go,” start timing. You need to: 1. Stand up. 2. Walk at your normal, comfortable pace to the 10-foot line. 3. Turn around. 4. Walk back. 5. Sit down again fully.

- Stop the watch when you’re seated.

- What the Results Mean: Another key number from the CDC: if it takes $\ge$12 seconds to complete the TUG, you’re at an increased risk for falling.

Test 7: The Gait Speed Test (The ‘Sixth Vital Sign’)

- What It Tracks: Your walking speed. It sounds simple, but it’s such a powerful predictor of future health, functional decline, and… well, everything, that many doctors call it the “sixth vital sign”.

- How to Perform:

- You need a hallway. Measure out 10 meters (32.8 ft).

- Mark a start line (0m), a line at 2m, a line at 8m, and the end (10m).

- Here’s the trick: You start before the 2m line, walk at your “normal, comfortable pace,” and a friend times you only for the middle 6 meters (between the 2m and 8m marks). This way, you’re not timing the start/stop, just your cruising speed.

- Calculate: $Speed (m/s) = 6 \text{ meters} / \text{time in seconds}$.

- Simpler version: Just time a 4-meter (13 ft) walk and divide 4 by the time.

- What the Results Mean: The magic number is 1.0. A gait speed of $< 1.0 \text{ m/s}$ is linked to increased fall risk and poor outcomes. A speed $< 0.8 \text{ m/s}$ predicts further functional decline.

Test 8: The Functional Reach Test (FRT)

- What It Tracks: Your “margin of stability.” How far can you reach for something before you lose your balance and have to take a step?.16

- How to Perform:

- Tape a yardstick to the wall, level with your shoulder.

- Stand right next to the wall (not touching it) and make a fist with the hand closer to the wall. Raise that arm so it’s parallel to the floor (90 degrees).

- Have a partner note the starting number on the yardstick at your 3rd knuckle.

- Now, “Reach as far as you can forward without taking a step.” No falling into it!.

- Your partner notes the new number. The score is the difference (in inches).

- What the Results Mean: This is all about your forward-moving “bubble” of safety. A score of $< 7$ inches (18.5 cm) flags a significant fall risk, especially for frail individuals.

Test 9: The Clock Reach

- What It Tracks: This is a dynamic, multi-directional test. It checks your ability to shift your weight and control your body in different directions, all while standing on one leg.

- How to Perform:

- Stand on one leg (use a chair for light, “fingertip” support if you need it).

- Imagine you’re at the center of a big clock on the floor.

- With your non-standing leg, reach with your foot to gently tap “12 o’clock” (straight ahead), then bring it back to center.

- Tap “3 o’clock” (to the side), then back to the center.

- Tap “6 o’clock” (behind you), then back to the center.

- Switch legs and repeat, tapping 12, 9, and 6 o’clock.

- What the Results Mean: This is a simple pass/fail. Can you do it smoothly? Or do you lose your balance, have to put your foot down, or stumble? This is a great test of coordination.

Category 3: Neurological Coordination (Checking the ‘Editor’) (Tests 10-12)

This last group is different. We’re not timing you (mostly). We’re looking at the quality of your movement. Are your actions smooth and accurate, or clumsy and jerky? This is our most direct check-in with that “movement editor”—the cerebellum.

Test 10: The Finger-to-Nose Test

- What It Tracks: This looks for dysmetria—that “overshoot/undershoot” problem. It’s a classic sign of cerebellar dysfunction.

- How to Perform:

- Sit or stand. Hold one arm straight out to your side.

- From there, bring your index finger in to touch the very tip of your nose.

- Go back out to the side.

- Repeat this several times, getting faster.

- Advanced: Try it with your eyes closed. Now you’re relying 100% on that internal GPS.

- What the Results Mean: A “pass” is smooth and on-target every time. A “fail” is dysmetria: you miss your nose, hit your cheek, or have to make a jerky “correction” mid-flight to find the target.

Test 11: The Heel-to-Shin Test

- What It Tracks: This is the same test, but for your lower body. It’s checking for coordination and ataxia.

- How to Perform:

- Sit on the edge of a chair or bed.

- Place the heel of one foot on your opposite knee.

- Now, smoothly and in a straight line, slide that heel all the way down your shin to your ankle.

- Lift the heel back to the knee and repeat a few times.

- What the Results Mean: A “pass” is a smooth, straight line. A “fail” is ataxia: your heel wobbles side-to-side, or you can’t keep it on your shin at all.10 This is another strong sign pointing to the cerebellum.

Test 12: The Rapid Alternating Movements (RAM) Test

- What It Tracks: This tests for something called dysdiadochokinesia (I know, it’s a mouthful!). It just means the inability to do rapid, alternating movements. It’s another highly specific sign of cerebellar trouble.

- How to Perform:

- Sit down and put your hands on your thighs.

- As fast as you possibly can, “slap” your thighs, alternating between your palms (palm down) and the back of your hands (palm up).

- Do this for 10-15 seconds.

- What the Results Mean: A “pass” is fast, rhythmic, and even. A “fail” is the “clumsy” factor: the movements are slow, irregular, arrhythmic, or one hand just can’t keep up.

So, now you’ve got this complete picture. And you can start to see why you might be unsteady.

- Fail the 5TSTS? Maybe it’s just a strength problem.

- Fail Romberg (eyes closed)? It’s a proprioceptive (GPS) problem.

- Fail tests 10-12? That points more specifically to the cerebellum (the ‘editor’).

This is why this toolkit is so powerful. It helps you, or your doctor, figure out what to work on.

So… How’d I Do? Decoding Your ‘Score’

Okay, you did the tests. Now what? The numbers are useless without context. Here is a guide to the benchmarks that clinicians and researchers use.

Your Brain & Body ‘Vital Signs’: A Guide to the Numbers

This table brings together the data from multiple clinical studies. This isn’t for you to diagnose yourself. It’s to help you see where you are today and, most importantly, to track your progress over time.

Table 1: At-Home Brain & Body “Vital Signs” – Normative Data

| Test | Age Group | Average / “Healthy” Score | “At-Risk” / See a Doctor | Source(s) |

| Tandem Stance | All Older Adults | Able to hold > 10 seconds | Cannot hold for 10 seconds | 5 |

| Single-Leg Stance (Eyes Open) | 40-49 yrs | ~40 seconds | < 20 seconds (general red flag) | 29 |

| 50-59 yrs | ~37 seconds | < 10 seconds (fall risk) | 37 | |

| 60-69 yrs | ~27 seconds | 3 | ||

| 70-79 yrs | ~15 seconds | 3 | ||

| 80-99 yrs | ~6 seconds | 3 | ||

| Five Times Sit-to-Stand (5TSTS) | 40-49 yrs | ~7.6 seconds | > 16 seconds (fall risk) | 60 |

| Timed Up & Go (TUG) | All Older Adults | < 10 seconds (Healthy) | $\ge$ 12 seconds (fall risk) | 41 |

| Gait Speed (“Sixth Vital Sign”) | 60-79 yrs | > 1.0 m/s | < 1.0 m/s (Fall risk, poor outcomes) | 69 |

| < 0.8 m/s (Functional decline) | 61 | |||

| Functional Reach (FRT) | 41-69 yrs | ~14-15 inches | < 7 inches (High fall risk) | 16 |

| 70-87 yrs | ~10-13 inches | 101 |

Look at that data for the Single-Leg Stance. It’s a perfect, measurable snapshot of aging. The average hold time in your 40s is ~40 seconds. By your 70s, it’s ~15 seconds. By your 80s, it’s ~6 seconds. The decline accelerates after 60. This isn’t to scare you! It’s to motivate you. This is why we train in our 40s and 50s—before the big drop-off.

What ‘At-Risk’ Really Means (And What It Doesn’t)

First, take a breath. An “at-risk” score—like a 13-second TUG test —is NOT a diagnosis. It is not a crystal ball. It is not a verdict.

It is a “check engine light.”

That’s it. It’s a beautiful, clear signal from your body that one of those systems—strength, sensory, or coordination—is declining. It’s a powerful, objective cue to take action and, yes, probably go chat with a physical therapist.

Interpreting the Coordination Tests (The ‘Pass/Fail’ Grade)

The cerebellar tests (10-12) aren’t timed. They’re pass/fail.

- A “Pass” = smooth, accurate, rhythmic movement.

- A “Fail” = you clearly see:

- Dysmetria: Missing your nose.

- Ataxia: Your heel wobbles all over your shin.

- Dysdiadochokinesia: Clumsy, arrhythmic hand-slapping.

A “fail” on these is a more specific neurological sign. It points strongly to the cerebellum, your “movement editor”.37 This is something you should definitely bring up with a neurologist.

Myth vs. Fact: Let’s Bust Some Common Beliefs

- Myth 1: Falling is just a normal, inevitable part of getting old.

- Truth: Nope. It’s common, but not inevitable. It’s a sign of an underlying, often treatable, issue: weak muscles, an inner ear problem, medication side effects, or a chronic condition. Balance is a skill you can improve.

- Myth 2: Brain decline is guaranteed after 60.

- Truth: Absolutely not. Dementia is not a normal part of aging. Plenty of people live into their 90s sharp as a tack. You have a massive amount of control over your risk factors.

- Myth 3: What’s good for your heart is different from what’s good for your brain.

- Truth: What’s good for your heart is good for your brain. Period. Your brain is a blood-guzzling organ. A heart-healthy diet and regular exercise are two of the best things you can do for both.

The Best Part: You Can Get Better. Your Action Plan.

The Best News: Balance Is a ‘Trainable’ Skill

This is the whole point. This is the empowering part. Balance is not a fixed state; you just “lose.” It is a trainable skill.

Your brain has this amazing ability called neuroplasticity—it can literally adapt, rewire, and change based on what you ask it to do. You can improve your balance, strength, and coordination at any age.2 Physical therapists are experts in this. One study on a 12-week balance program found it was not only effective but also motivating and… fun.

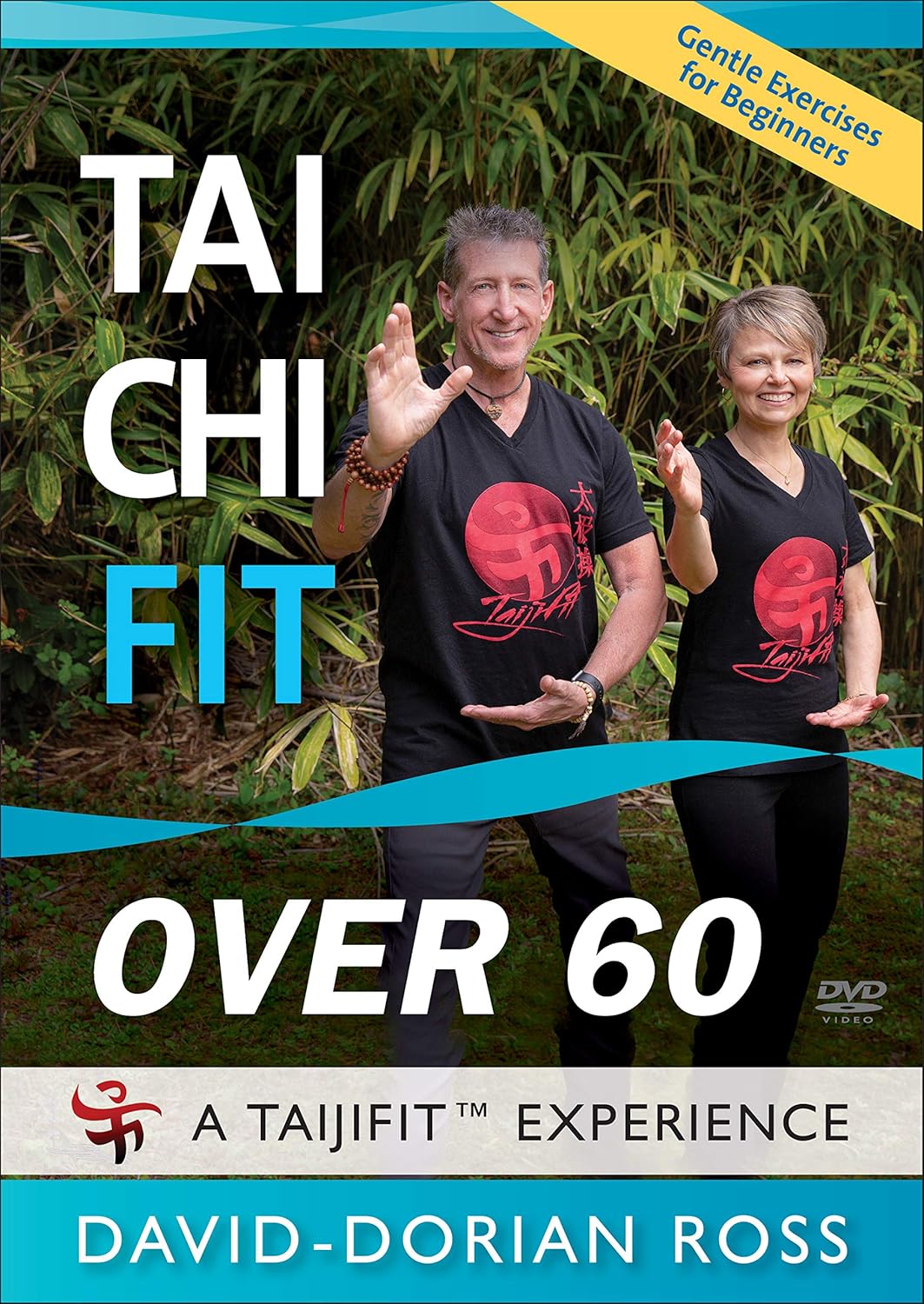

The ‘Gold Standard’ Intervention: Tai Chi

If I could only give one prescription, this would probably be it. Tai Chi is a gentle, flowing martial art that’s basically a “two-for-one” for your brain and body.

- For the Body: It’s proven to improve balance and lower-limb strength, which directly reduces fall risk. A 2024 meta-analysis confirmed it: Tai Chi positively affects balance in healthy older adults.

- For the Brain: This is the amazing part. A 24-week study on folks with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) found the Tai Chi group had significant improvements in cognitive function and memory.

- The How: Why does it work so well? Research suggests Tai Chi increases your levels of BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor). Just think of BDNF as “Miracle-Gro” for your neurons. It helps them grow, survive, and connect. It also helps regulate the parts of your brain tied to cognitive control.

Your At-Home ‘Balance Gym’: 5 Key Exercises to Start Today

A good plan hits all the systems: strength, balance, and coordination. The World Health Organization (WHO) is clear: for adults 65+, the recipe is 150+ minutes of moderate aerobic activity (like brisk walking) per week, 2-3 days of strength work, and 3+ days of balance-focused exercises.

Here’s how you can improve your scores on those tests.

- Strength (To fix your 5TSTS/TUG score):

- Sit-to-Stands (Chair Squats): The best way to get better at the Sit-to-Stand test is to… do sit-to-stands. Practice the movement slowly. Stand up from your chair, no hands. Sit back down with control. Aim for 3 sets of 10.

- Leg Raises (Side & Back): Stand behind a chair. Slowly lift one leg straight out to the side. Hold for 3 seconds. Lower. Then lift it straight back. Do 10-15 reps per leg.

- Static Balance (To fix your SLS score):

- Practice Single-Leg Stance: Seriously, just practice the test. Do it while brushing your teeth. Hold onto a counter. Aim to add 2 seconds every few days.

- Progression: Once 30 seconds is easy, try it standing on a pillow.

- Dynamic Balance (To fix your Gait/Tandem score):

- Heel-to-Toe / “Tightrope” Walk: Practice the Tandem Stance, but in motion. Walk a straight line in your hallway, heel-to-toe.

- Proprioception (To fix your Romberg/Clock score):

- Weight Shifts: Stand with feet hip-width apart. Slowly shift your weight all the way to your right side, letting your left foot get light. Hold for 20 seconds. Shift left.

- Tree Pose (Yoga): Stand on one leg, place the sole of your other foot on your inner calf (not the knee!). Hold for 20-30 seconds.

- Coordination (To fix your Cerebellar scores):

- The tests are the exercises. Practice slow, mindful Finger-to-Nose touches. Practice controlled Heel-to-Shin slides. You are literally retraining that “movement editor”.

Beyond Exercise: The Holistic Habits of a ‘Balanced’ Brain

You can’t balance-train your way out of a bad diet or no sleep.

- Get Moving: That 150 minutes/week of aerobic exercise (brisk walking, swimming, biking) is non-negotiable. It’s one of the best-proven ways to support brain function.

- Eat Smart: A heart-healthy, brain-healthy diet. Fruits, veggies, whole grains, lean proteins. A simple vitamin B12 deficiency can directly impact your cerebellum and cause balance problems.

- Stay Engaged: Keep that brain busy. Read, do puzzles, learn something new, stay social.

- Protect Your Head: Wear the helmet when you bike. Seriously. And review your medications with your doctor—many common drugs can cause dizziness as a side effect.

A Few Tools That Might Make This Easier

You don’t need any of this to get started. Honestly, your own body and a sturdy chair are the only “gym” you need. But if you’re looking for ways to support your practice, make it a little safer, or add a new challenge, here are a few things people find really helpful.

1. A Foam Balance Pad

Remember how we talked about standing on a pillow to make the Single-Leg Stance harder? This is the “official” version. It’s a thick, squishy foam pad that’s designed to be unstable. It’s a fantastic, safe way to challenge your “internal GPS” (proprioception) and strengthen all those tiny muscles in your ankles and legs.

2. A Wobble Cushion / Balance Disc

This is a similar idea but a step up. It’s an inflatable disc that you can stand on (or sit on to help with core strength). Because it’s filled with air, it’s very wobbly and forces your brain to make constant, tiny adjustments. It’s great for progressing your Single-Leg Stance or even just standing on two feet.

3. A Simple Digital Stopwatch

This one’s basic, but it’s key. For the 5TSTS, TUG, and Gait Speed tests, “feeling” the time isn’t good enough. You need an objective number. A simple, large-display stopwatch (like one a coach would use) is cheap, easy to use, and lets you see real, measurable progress.

4. A “Tai Chi for Beginners” Program (DVD or Book)

We talked a lot about Tai Chi being the “gold standard” for a reason. If you’re not ready to join a class, a beginner’s DVD or a well-illustrated book can be a great way to learn the basic, gentle movements in the privacy of your living room.

5. A Safety Gait Belt

This is for anyone who is acting as a “spotter” for a loved one. If you’re nervous about helping someone with these tests, a gait belt is what the pros use. It’s a simple, secure belt that goes around the person’s waist, giving you a safe and sturdy place to hold onto, so you can prevent a fall without grabbing their arm and pulling them off balance.

Your Next Steps: When to ‘Track’ and When to Talk to a Pro

How to Track Your Brain-Balance Score

Don’t do these tests every day; you’ll drive yourself nuts. Pick a day. Do them once per month.47 Write your scores in a notebook.

- Record the time for the SLS, 5TSTS, TUG, and Gait Speed.

- Record “Pass” or “Fail” for the Tandem, Romberg, and the 3 Coordination tests.

- You’re looking for trends. A consistent downward trend is a signal to act. A consistent upward trend (because you’ve been practicing) is a reason to celebrate.

When to Call Your Doctor: A Clear Guide

This toolkit is for screening, not diagnosis. You should call a healthcare professional if you see any of these red flags:

- A Sudden Change: If your balance or coordination gets suddenly worse (like, over a day or two), or it comes with a severe headache, vision changes, or new weakness, seek medical care immediately.

- You Score “At-Risk”: If your scores are consistently in that “at-risk” column. The big three are:

- Timed Up & Go (TUG): $\ge$12 seconds

- Five Times Sit-to-Stand (5TSTS): >16 seconds

- Tandem Stance: Cannot hold for 10 seconds

- You “Fail” the Coordination Tests: If you consistently show signs of Dysmetria (missing the nose), Ataxia (heel slipping), or Dysdiadochokinesia (clumsy hands).

- You Experience Dizziness or Vertigo: If you have a persistent feeling that the room is spinning. This could be a very treatable inner ear (vestibular) problem.

Think of it this way: a Physical Therapist is your first call for “at-risk” scores on the strength and balance tests (Tests 1-9). A Neurologist is the right call for “fails” on the coordination tests (10-12) or sudden, severe symptoms.

The Empowering Takeaway: Your Balance Is a Conversation

Your balance isn’t a thing you have; it’s a thing you do. It’s a dynamic, living system. It’s a constant “conversation” between your brain, your body, and the world.

Feeling unsteady is just a sign that the conversation is breaking down.

This toolkit is just a way to listen in on that conversation. The action plan is your way to join in. You have the power to strengthen the signal, sharpen the editor, and, step by step, retrain the entire system. You have the power to keep yourself standing tall.